In the weed world, we have developed nearly infinite possibilities when it comes to consumption of the cannabis plant. Among those possibilities, no single category has seen such an explosion in diversity as that of cannabis concentrates. Concentrates represent a massive industry and extraction methods have evolved accordingly to meet the demand for diverse extracts. Of these extracts we have everything from resins, rosins, kiefs, sauces, distillates, hashes, waxes, budders, shatters, tinctures, oils and more.

With such variety, comes a need for an array of different methods in order to produce them.

In this first of a 2 part series of articles, we’ll go over the 4 main extraction methods as well as briefly touch on which method best suits the extracted product being produced. Part 2 will be more focused on extracts themselves.

Here are brief overviews of the 4 most commonly used extraction methods used on the market today.

Supercritical CO2 (Solventless extraction)

Supercritical CO2 is very common as an extraction method in the food and pharma industries. Once heated and placed under high pressure, CO2 extraction is one of the most efficient ways to extract specific compounds from a wide range of materials. Everything from decaffeination of coffee, extraction of hops in beer making, to extracting different molecules from cannabis plants can be done with high pressure supercritical CO2.

Some distinct benefits to this type of extraction are that it uses a closed loop system which allows CO2 to be filtered and recycled to be used again, making it an efficient process over all.

One notable drawback however is the equipment costs and high pressures – upwards of 5,000psi -are needed for this process. Most smaller manufacturers of cannabis extracts simply can’t afford it, which makes the next extraction technique on our list far more common in the cannabis industry.

Some of the best products made using CO2 include ranges of: oils, tinctures, and waxes. The key differences in CO2 are cost of production and the need for further refinement if you plan on producing something other than the concentrations outlined above.

Hydrocarbons (butane/propane/hexane)

Hydrocarbon extraction is the most common and versatile method of extraction currently used in the cannabis industry. Nearly all oil based extracts on the market can be produced using a hydrocarbon process. The most common gases used for extraction are butane and propane, however in rare cases, gases such as hexane may also be used. The main advantage to the hydrocarbon process is that it is highly customizable. By altering the properties of the gases – temperature and pressure in conjunction with solvent polarity – lab techs can select what cannabinoids, terpenes, and flavonoids are collected based on molecular structure, and which ones are stripped away with the water content and excess plant matter to achieve the raw oil needed to produce any given extract from full spectrum, to broad, to isolate (CO2 can also achieve this).

Even though it’s the most popular method, it also requires more manual labor than other extraction processes, as well as more monitoring to get good product consistency. It’s also risky if done without the right knowledge or equipment. As the gases are inflammable and explosive, many safety protocols must be in place. The cost for the surrounding infrastructure and permits to use hydrocarbon is often greater than the equipment itself, but if everything is done right, the versatility of the process can produce nearly all the extracts available on the market in very large quantities, allowing for a fair ROI overtime.

There is a bias around hydrocarbons as some claim that some toxic residuals remain on the finished product. This can sometimes be true in illegal unregulated facilities, but this rarely, if ever, occurs in licenced facilities which use hydrocarbons. An evaporation phase is built into the process to remove any residual hydrocarbons to an industry standard of 50 PPM in the finished product or less. This amounts to less than the average hydrocarbon content of the air we breathe in a modern city.

Ethanol

Ethanol (alcohol) is pure, food grade alcohol at near 100% concentration which is known as an azeotropic substance, because it still contains a tiny amount of water. Ethanol extraction is one of the oldest forms of extractions known to history, coming in at a close second to solventless extraction. Ethanol extraction is a process that does not require high pressures or advanced post-processing techniques, making it a technique that is quite cost effective overall. In terms of a solvent, ethanol also enjoys the status of being the lowest cost solvent to purchase in bulk.

As with any other method however, there are some limitations to ethanol’s utility. The first is you need a lot of ethanol due to the average rate of evaporation. There are federal regulations within Canada that limit the amount you can buy in one transaction,as opposed to no such restrictions existing in the USA. This regulation of sale may limit some mass production floors in Canada who may use ethanol to being small batch producers of extracts. But at a lower overall cost, this may be more economic for some smaller facilities.

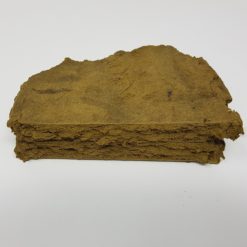

The type of raw extract that ethanol produces is called crude oil, and it’s exactly what the name suggests. A raw cannabis oil product that must be further refined into whatever extract is desired. Ethanol also destroys most terpenes and phytochemicals, leaving only cannabinoids behind – making it more ideal for the production of isolates.

Solventless

Solventless extraction is a class that includes only a few simple methods: dry heat, grinding, hot water, and pressure. This form of extraction is likely to be the most ancient and easy to do.

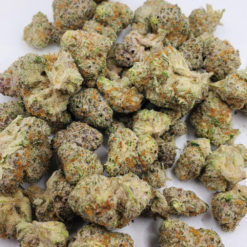

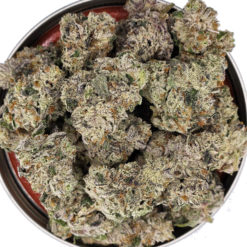

If you own a multi-chamber grinder, then you’re an active solventless cannabis extractor. The “fluff” that gathers at the bottom is essentially a concentrate commonly known as kief. This extract can be compressed and rolled into a hash ball, used as is, or heated on a hot pressure press to produce rosin (as can regular weed buds, but kief makes a much more pure and concentrated rosin).

Another way to produce solventless extracts is by using heat and pressure in the form of a heat press, or even a standard straightening iron normally used for hair. To do this, place your raw buds between 2 pieces of wax paper, squeeze and heat your buds for a few seconds, then scrape the rosin off the wax paper. Rosin can be smoked as is and is up to 80% more potent that the baseline of the type of cannabis it was initially extracted from while also retaining the majority of its properties.

Finally, hot water may also be used as an extract to make cannabis teas. Yes, you read that correctly. If warm milk or some sort of binding fat is added, the fat extracts the ground bud into the water, while the heat begins to convert the cannabinoids into their non-acidic, active forms such as THCA into THC. This method is far less common, but may serve well those who are looking for a mild full spectrum extract that can be made at home with a cannabis strain of choice.

We hope you enjoyed this brief overview of how cannabis extracts are made!

Before you go, make sure to check out our wide selection of concentrates in our store. Now that you know a little more about how they’re made, you’ll be all that more impressed by what we have!

Stay tuned for our next post in this 2-part series where we go a little more in depth on extracts themselves.

References

Cannabis Concentrates Guide by PotGuide.com

The best cannabis concentrates for beginners Leafly Staff by Leafly Staff, 2019

Part One:Behind The Curtain Of Industrial Cannabis Extracts, Cannabis Science Podcast, 2019 https://open.spotify.com/episode/3c4GMXm9lzORuBPbyoLMf8?si=itdJwZdOQUC7f093ujWm_Q

Extracting Cannabis with Ethanol – Good Idea or Drunk on Fumes – Cannabis Science Podcast

Extraction Explained: Solventless vs Hydrocarbon – The Truth About Removing Residual Solvents, Precision Extraction Solutions, 2020

Ethanol vs. Hydrocarbon vs. Co2 vs. Solventless Extraction Processes: What’s the Best for My Laboratory?, by Dylan Thiel, 2020